Who Are You?

When I get home from school, I sit down on my couch as my small and furry mutt of a dog comes over and hops up on my lap. As I pet him, I look closely at his features. He has pointy ears, a kinked tail, and sharp, slicing teeth. These features all make him look very different from me and all other humans. But, on second glance, he actually has a lot of things in common with humans. We both have hair, two eyes, four limbs, and a bony skeleton that anchors our muscles. So, what is it about a dog that makes it not human but similar enough that we are both mammals?

When I get home from school, I sit down on my couch as my small and furry mutt of a dog comes over and hops up on my lap. As I pet him, I look closely at his features. He has pointy ears, a kinked tail, and sharp, slicing teeth. These features all make him look very different from me and all other humans. But, on second glance, he actually has a lot of things in common with humans. We both have hair, two eyes, four limbs, and a bony skeleton that anchors our muscles. So, what is it about a dog that makes it not human but similar enough that we are both mammals?

Have you ever wondered how your cat, dog, bird, lizard, or fish is related to you? Don’t worry if you don’t know—there’s a relatively easy way to find out. Luckily, animal bodies today are like living history books. They tell stories about the evolutionary past. Paleoanthropologists can look at human fossils and even older animal fossils to learn about a story that goes back at least 500 million years. The story is about the history of our lineage or the line of species that led to humans, Homo sapiens. Over millions of years, the story takes us from the origin of vertebrates (animals with backbones) to the present day. Along the way, it looks at our ancestors and the descendant species that eventually produced humans.

Have you ever wondered how your cat, dog, bird, lizard, or fish is related to you? Don’t worry if you don’t know—there’s a relatively easy way to find out. Luckily, animal bodies today are like living history books. They tell stories about the evolutionary past. Paleoanthropologists can look at human fossils and even older animal fossils to learn about a story that goes back at least 500 million years. The story is about the history of our lineage or the line of species that led to humans, Homo sapiens. Over millions of years, the story takes us from the origin of vertebrates (animals with backbones) to the present day. Along the way, it looks at our ancestors and the descendant species that eventually produced humans.

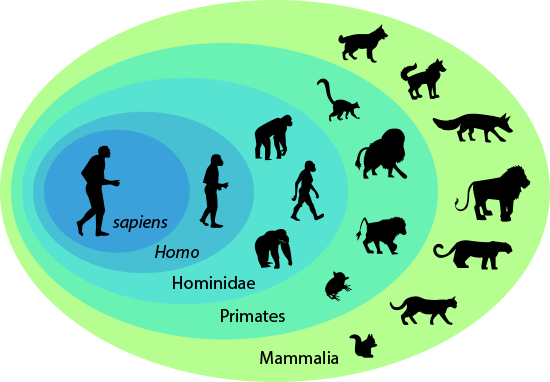

Living animals that share some of our features can help us learn what other animals we are related to. They also help us learn about how far back those features evolved. For example, humans share a head and a backbone with other vertebrates (like fish). We share arms and legs with tetrapods (vertebrates with four limbs, like lizards or birds). We also share hair with mammals (like cats or dogs) and grasping hands with primates (like the monkeys or orangutans you might see at the zoo). The animals we share more features with, like primates, are more closely related to us.

The “Tree of Life”

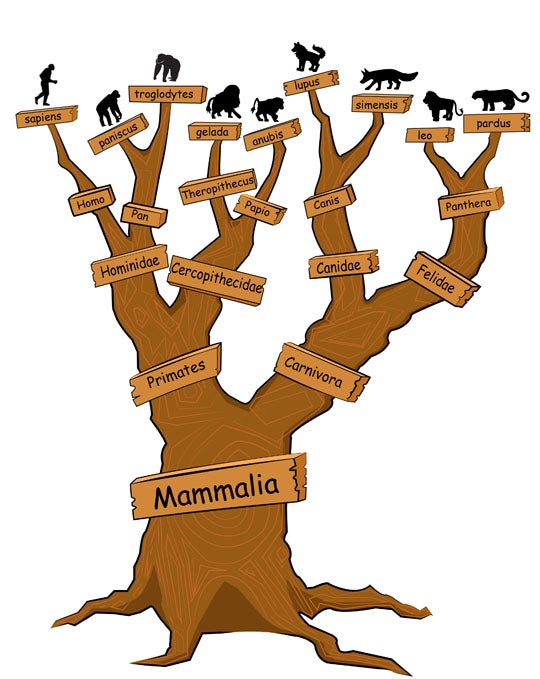

When scientists place humans or any species within groups based on similar features, they are doing the science of taxonomy. So, modern humans (species Homo sapiens) are in the human genus (genus Homo), which is a part of the hominid family (family Hominidae). Hominids are primates (order Primates) and related to all other mammals (class Mammalia).

When scientists go a step further and study the history of features that link biological groups based on their evolution, they are doing phylogenetics. So, while a taxonomist might realize that hair unites all mammals, a phylogeneticist might wonder when and how hair evolved in mammals."

Both taxonomy and phylogenetics are used to understand the evolution of a group of animals. So, imagine a tree, like a big oak tree. You can think of the very tips of the branches as species, like Canis familiaris (your dog) or Canis lupus (the grey wolf). The larger branches that connect these tips are genera (the plural form of genus). So the large branch that connects Canis familiaris and Canis lupus is the genus Canis. Genera are connected by even larger branches which we call families.

Both taxonomy and phylogenetics are used to understand the evolution of a group of animals. So, imagine a tree, like a big oak tree. You can think of the very tips of the branches as species, like Canis familiaris (your dog) or Canis lupus (the grey wolf). The larger branches that connect these tips are genera (the plural form of genus). So the large branch that connects Canis familiaris and Canis lupus is the genus Canis. Genera are connected by even larger branches which we call families.

Our two Canis species belong to the family Canidae, which includes dogs, wolves, and foxes. Canidae is one of several families in the order Carnivora (which includes dogs, cats, bears, seals, and others). The orders would make up the very largest branches, or the upper part of the trunk, where the trunk splits into different parts of the tree.

Finally, all orders of mammals are placed in the class Mammalia. You are mammal too! In our example, the class is the trunk of the tree that connects all mammal groups, including our species, Homo sapiens.

Adding dates to the “Tree of Life”

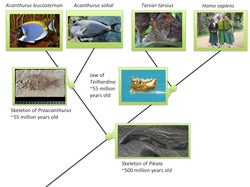

Now, you might be wondering, how old are each of these branches, and how old is the trunk of the tree? Scientists can use the fossil record to tell how long ago different branches on the tree of life split from one another. Let’s use Homo sapiens as an example to work our way back up the tree from the base, now that we’ve worked our way down from dogs and wolves.

Now, you might be wondering, how old are each of these branches, and how old is the trunk of the tree? Scientists can use the fossil record to tell how long ago different branches on the tree of life split from one another. Let’s use Homo sapiens as an example to work our way back up the tree from the base, now that we’ve worked our way down from dogs and wolves.

Fossils of small shrew-like mammals show us that the very bottom of the tree (class Mammalia) is at least 225 million years old. I say “at least” because the first fossils of a group are probably only a minimum age for when they first evolved. New fossils could be discovered in the future that push the group’s first appearance back in the time, making it older. So while mammals might have appeared before 225 million years ago, these small fossils give us a rough minimum age for the origin of mammals.

The large branch (order Primates) to which humans belong is at least 55 million years old, based on fossils from Asia. Archicebus and Teilhardina were small (less than one ounce) primates that lived in Asia 55 million years ago. They probably behaved a lot like modern tarsiers (http://www.arkive.org/spectral-tarsier/tarsius-tarsier/).

Higher up the primate branch, we find that humans are placed in the great ape family, called Hominidae. This group also includes chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans. The earliest fossils of a great ape ancestor are 24 million years old. This primate, called Rukwapithecus, was found in Tanzania in 2013. Later in time, fossils from East and Central Africa show us that humans split off from the other great apes around seven million years ago. These fossils are of early human relatives, and they belong to the genera Sahelanthropus, Orrorin, and Ardipithecus.

Finally, the human genus, Homo, originated at least 2.8 million years ago. This date is based on a jawbone from Ethiopia that was discovered by Arizona State University scientists in 2013. Our species, Homo sapiens, is even younger. The earliest fossils of Homo sapiens are only 200,000 years old. While 200,000 years might seem long, it’s not on the scale of evolution. Humans are newcomers to planet Earth.

Bibliographic Details

- Article: Who Are You?

- Author(s): John Rowan

- Publisher: Arizona State University Institute of Human Origins Ask An Anthropologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask An Anthropologist

- Date published:

- Date modified:

- Date accessed: March 26, 2025

- Link: https://askananthropologist.asu.edu/stories/early-human-history

APA Style

John Rowan. (). Who Are You?. Retrieved 2025, Mar 26, from {{ view_node }}

American Psychological Association, 6th ed., 2nd printing, 2009.

For more info, see the

APA citation guide.

Chicago Manual of Style

John Rowan. "Who Are You?." ASU - Ask An Anthropologist. Published . Last modified . https://askananthropologist.asu.edu/stories/early-human-history.

Chicago Manual of Style, 17th ed., 2017.

For more info, see the

Chicago Manual citation guide.

MLA Style

John Rowan. Who Are You?. ASU - Ask An Anthropologist. , {{ view_node }}. Accessed March 26, 2025.

Modern Language Association, 8th ed., 2016.

For more info, see the

MLA citation guide.

Be Part of

Ask An Anthropologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a volunteers page to get the process started.