When Did Our Brains Get Big?

When we are born, we have big heads and barely any body hair. As we grow up, our brains get much bigger, and we learn how to talk and walk on two legs. But aside from these features, not much makes human babies very different from young chimpanzees. When studying humans, the things that set us apart form other species can be very important.

When we are born, we have big heads and barely any body hair. As we grow up, our brains get much bigger, and we learn how to talk and walk on two legs. But aside from these features, not much makes human babies very different from young chimpanzees. When studying humans, the things that set us apart form other species can be very important.

Scientists look for human features in fossils to identify our ancestors. Large brains, complex tools, and bipedalism are some of these features. People used to think that these features all appeared at the same time. But when scientists found more fossils, we learned something very important about our evolution. We learned that big brains, the ability to make stone tools, and the ability to walk on two legs each evolved separately.

Before brains got big

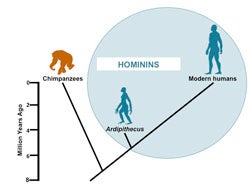

The last common ancestor of humans and chimpanzees lived about six to eight million years ago. Any species that evolved after this last common ancestor, but were more related to humans than to chimps, are known as hominins.

The bodies of hominins are different from chimpanzees because hominins walked on two legs. Brain size, on the other hand, didn't change much for the first few million years of human evolution. In fact, one of the early hominins, Ardipithecus ramidus, had a brain that was even smaller than a chimpanzee brain. These early hominins resembled humans only in the fact that they were bipedal. Despite their small brains, some of them may have used simple stone tools to butcher scavenged animals.

The bodies of hominins are different from chimpanzees because hominins walked on two legs. Brain size, on the other hand, didn't change much for the first few million years of human evolution. In fact, one of the early hominins, Ardipithecus ramidus, had a brain that was even smaller than a chimpanzee brain. These early hominins resembled humans only in the fact that they were bipedal. Despite their small brains, some of them may have used simple stone tools to butcher scavenged animals.

Blustery days and bigger brains

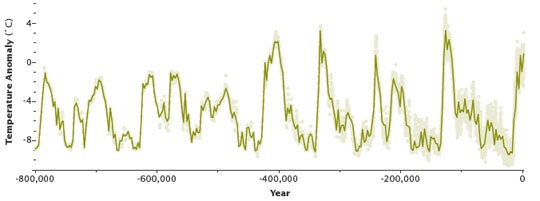

As our closest ancestors evolved, brain size began to increase substantially in members of our own genus, Homo. Scientists believe that there is a link between brain size and how variable the climate is. The logic is that living in a variable climate makes life unpredictable. When climate is unpredictable, food and water are more difficult to find. It may take more time and effort to find them. Having a large brain allows animals to think their way through these unpredictable conditions.

About two million years ago, the climate began to be more variable than it had been before that. This variability in climate coincided with brain size increases in early Homo. Bigger brains allowed early Homo species to survive in variable environments. For example, bigger brains may have allowed Homo to be a more strategic hunter or scavenger.

The bodies of early Homo were also more human-like than those of early hominins. This may have allowed early Homo to travel and run for long distances, perhaps even running their prey to exhaustion. Early Homo also had more complex stone tools. Such tools would have made killing and butchering animals easier.

The trend of climatic instability continued from 800,000 to 200,000 years ago. The greatest variation in climate in all of human history occurred during this time. This also coincided with the greatest increases in brain size, and brains eventually reached the size they are in modern humans. One late Homo species, the Neanderthal, grew brains that even exceeded modern human brain size. Neanderthals are associated with complex stone tools, and they were excellent hunters.

The trend of climatic instability continued from 800,000 to 200,000 years ago. The greatest variation in climate in all of human history occurred during this time. This also coincided with the greatest increases in brain size, and brains eventually reached the size they are in modern humans. One late Homo species, the Neanderthal, grew brains that even exceeded modern human brain size. Neanderthals are associated with complex stone tools, and they were excellent hunters.

How did our brains get bigger?

Brain growth and upkeep is expensive, as it requires large amounts of high-energy food. So for our ancestors to develop bigger brains, they needed more high-energy foods. Scientists believe that meat played a major role in the evolution of our brain size. Meat is rich with calories and protein, which makes it a perfect food for fueling brains. Which meal do you think contains more protein and calories: raw carrots and celery or a steak and baked potato?

Cooking food may also have been important in brain size increases. Cooking increases the amount of energy that can be extracted from food. As we began cooking our food, our brains got bigger and the size of our guts got smaller. Cooking food makes the digestion process easier for our bodies. We needed less time for digestion to occur, and so our intestines became shorter. The energy that was once used to grow and maintain the gut could now be funneled toward the brain.

Having buddies builds the brain

If you use social media then you may have hundreds of Facebook friends or Twitter followers in your social network. Social networks existed long before the internet. A social network is a group of people that interacts. It can consist of friends, family members, and other members of society.

Humans are very social animals. Having large social networks promotes cooperation among us. Cooperation is part of what makes us human and allows us to live in groups. Think about how many people you interact with on a daily basis. Some days, you would probably lose count of all the people you talk to.

Humans are very social animals. Having large social networks promotes cooperation among us. Cooperation is part of what makes us human and allows us to live in groups. Think about how many people you interact with on a daily basis. Some days, you would probably lose count of all the people you talk to.

We live in large groups and interact with many people, whether they are our friends or family members. How do we keep track of all these interactions? Some scientists believe that a large brain enables us to maintain such a large social network. Based on the size of our brains, our main social network should consist of about 150 people. Beyond this size, it is difficult to keep track of so many interactions. Many studies have confirmed that people generally have social networks of around 150 people.

Monkeys or apes, on the other hand, interact with only about 10 to 20 individuals per day, so their social networks are much smaller. An increase in brain size during human evolution would have resulted in an increase in the social networks of hominins.

Bibliographic Details

- Article: When Did Our Brains Get Big?

- Author(s): Halszka Glowacka

- Publisher: Arizona State University Institute of Human Origins Ask An Anthropologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask An Anthropologist

- Date published:

- Date modified:

- Date accessed: December 19, 2024

- Link: https://askananthropologist.asu.edu/stories/when-did-our-brains-get-big

APA Style

Halszka Glowacka. (). When Did Our Brains Get Big?. Retrieved 2024, Dec 19, from {{ view_node }}

American Psychological Association, 6th ed., 2nd printing, 2009.

For more info, see the

APA citation guide.

Chicago Manual of Style

Halszka Glowacka. "When Did Our Brains Get Big?." ASU - Ask An Anthropologist. Published . Last modified . https://askananthropologist.asu.edu/stories/when-did-our-brains-get-big.

Chicago Manual of Style, 17th ed., 2017.

For more info, see the

Chicago Manual citation guide.

MLA Style

Halszka Glowacka. When Did Our Brains Get Big?. ASU - Ask An Anthropologist. , {{ view_node }}. Accessed December 19, 2024.

Modern Language Association, 8th ed., 2016.

For more info, see the

MLA citation guide.

Learn more about the parts of the brain and what they do at Ask A Biologist's A Nervous Journey

Be Part of

Ask An Anthropologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a volunteers page to get the process started.