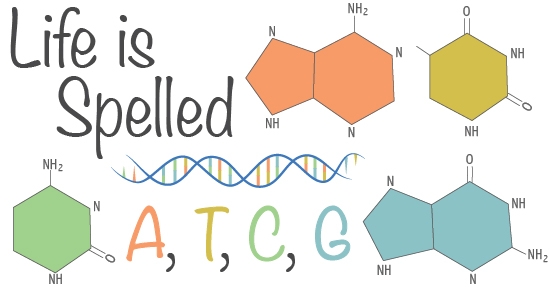

Life is Spelled A, T, C, G

Birds and squirrels chatter in the trees, bumblebees buzz around the flowers, and the dirt crawls with bugs and tiny microorganisms. The life outside your window and around the world is very diverse. It includes animals, plants, fungi, and bacteria. You can stand apart from all this life and admire it. However, you are a living organism—you also fit into the tree of life. Being alive unites us, and life itself would not be possible without a small molecule known as DNA.

The basics of DNA

DNA stands for deoxyribose nucleic acid. It is found in most cells and is made up of chemical compounds known as nucleotides. DNA has four nucleotides. They are adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T). Nucleotides are strung together into long sequences known as chromosomes, and each chromosome has thousands of genes. Together, these are the instructions for making an organism.

DNA stands for deoxyribose nucleic acid. It is found in most cells and is made up of chemical compounds known as nucleotides. DNA has four nucleotides. They are adenine (A), cytosine (C), guanine (G), and thymine (T). Nucleotides are strung together into long sequences known as chromosomes, and each chromosome has thousands of genes. Together, these are the instructions for making an organism.

You can think of these DNA sequence instructions as chemical sentences. The sequence ATCGGGTCA might say “make curly red hair,” and TTCGGGATCACACCACATGACCCG might say “make brown eyes.”

You and other humans have 23 pairs of chromosomes with about 20,000 genes. All of this DNA that makes you a human is known as your genome. Each of your cells holds your entire genome. This means each cell's DNA has over three billion nucleotides and is six feet long stretched out. This thin strand gets wrapped up very tightly so that it can fit into one of your cells. Unless you are an identical twin, no other living organism in the world has the same exact genome as you.

How DNA changes

You and your relatives have very similar genomes. However, species have very different DNA. The DNA sequences, types of genes, and number of chromosomes can all vary between species. But where do these differences come from?

Imagine trying to write one copy of the following sentence:

Imagine trying to write one copy of the following sentence:

“Put the cat in the hat.”

Copying this sentence one time probably isn’t too difficult. Now imagine copying it one thousand times. After so many repetitions, you might have one or two accidental mistakes – maybe “Put the cat on the hat” or “Pot the cat in the mat.”

In the same way, nature has to copy its chemical DNA sentences every time a cell divides. And nature is not perfect. Sometimes it writes one too many "A"s, forgets to add one "T," or writes a "C" instead of a "G." These accidental DNA sequence changes are called mutations. Most mutations are neutral. This means the mutation does not change the organism’s phenotype, or how it looks or behaves. However, every once in a while a mutation comes along that does change the phenotype.

How DNA evolves

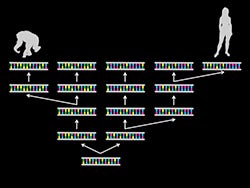

DNA is passed from parent to offspring, and new mutations can arise during this process. Your mother and father each gave you half of their DNA. In order to do this, their sex cells and the DNA inside of them were copied and divided during a process known as meiosis. If a copying error occurred, then this mutation was passed onto you. The mutation you acquired can then be passed onto your children who may acquire their own new mutations. And your children can then pass these mutations on to their children who may acquire their own new mutation. Imagine if this process continued over hundreds of generations. How many mutations do you think would occur? How much would the final DNA sequence have changed?

DNA is passed from parent to offspring, and new mutations can arise during this process. Your mother and father each gave you half of their DNA. In order to do this, their sex cells and the DNA inside of them were copied and divided during a process known as meiosis. If a copying error occurred, then this mutation was passed onto you. The mutation you acquired can then be passed onto your children who may acquire their own new mutations. And your children can then pass these mutations on to their children who may acquire their own new mutation. Imagine if this process continued over hundreds of generations. How many mutations do you think would occur? How much would the final DNA sequence have changed?

Mutations take time to accumulate. One or two generations will produce very few mutations. These may or may not change the phenotype. Also, the organisms will stay the same species. This is called microevolution.

On the other hand, more time will produce more mutations. After a very long time, one group of organisms may evolve into two distinct species. This is called macroevolution. Because mutations buildup over time, species that diverged 100 million years ago will have more mutations than species that diverged five million years ago. Thus, scientists can use DNA to tell one species from another.

Why DNA should matter to you

You can find your place on the tree of life by comparing your DNA to that of other closely related species. Humans are primates. Primates are mammals. And mammals are vertebrates. Therefore, looking at DNA sequences from other primates, mammals, and vertebrates is a good starting point. However, in order to do this, you first need genome sequences.

Sequencing a genome is like solving a jigsaw puzzle. There are hundreds of pieces that come together to make a picture. You first organize the pieces. Sometimes you separate the edge pieces and the middle pieces. Sometimes the piece color helps you know which part of the picture they fit into. However, in order to build the puzzle, you need to look at each piece individually and determine which two pieces fit together best based on the overall picture.

Sequencing a genome is like solving a jigsaw puzzle. There are hundreds of pieces that come together to make a picture. You first organize the pieces. Sometimes you separate the edge pieces and the middle pieces. Sometimes the piece color helps you know which part of the picture they fit into. However, in order to build the puzzle, you need to look at each piece individually and determine which two pieces fit together best based on the overall picture.

Similarly, scientists sequence genomes by first cutting the DNA into small pieces. Each piece is sequenced. Lastly, these separate sequences are put back together. Like a puzzle, fitting all these pieces together shows the whole genome sequence.

So far, over 13,000 complete genomes have been sequenced. Only a small fraction of these come from vertebrates, mammals, and primates. Most come from other types of organisms like worms or bacteria. Some sequences even come from creatures that are not technically alive, such as viruses. While DNA unites all organisms and helps us find our place on the tree of life, it is not exclusive to life. Nevertheless, without DNA, life would not be possible.

Bibliographic Details

- Article: Life is Spelled A, T, C, G

- Author(s): Genevieve Housman

- Publisher: Arizona State University Institute of Human Origins Ask An Anthropologist

- Site name: ASU - Ask An Anthropologist

- Date published:

- Date modified:

- Date accessed: February 5, 2026

- Link: https://askananthropologist.asu.edu/life-spelled-a-t-c-g

APA Style

Genevieve Housman. (). Life is Spelled A, T, C, G. Retrieved 2026, Feb 5, from {{ view_node }}

American Psychological Association, 6th ed., 2nd printing, 2009.

For more info, see the

APA citation guide.

Chicago Manual of Style

Genevieve Housman. "Life is Spelled A, T, C, G." ASU - Ask An Anthropologist. Published . Last modified . https://askananthropologist.asu.edu/life-spelled-a-t-c-g.

Chicago Manual of Style, 17th ed., 2017.

For more info, see the

Chicago Manual citation guide.

MLA Style

Genevieve Housman. Life is Spelled A, T, C, G. ASU - Ask An Anthropologist. , {{ view_node }}. Accessed February 5, 2026.

Modern Language Association, 8th ed., 2016.

For more info, see the

MLA citation guide.

Be Part of

Ask An Anthropologist

By volunteering, or simply sending us feedback on the site. Scientists, teachers, writers, illustrators, and translators are all important to the program. If you are interested in helping with the website we have a volunteers page to get the process started.